In a typical program that runs code and dynamically allocates the part of your memory on your hardware, it's mostly unknown how much memory you will use concurrently. This program can be anything from a website that you load up on your browser to a game that you play on lazy Saturday nights. So the implementation of garbage collection basically does is, it constantly searches and detects a memory that is not referenced(used) but allocated for the program and when it detects the aforementioned memory, it releases it so other processes can use that bit of space to run smoothly and makes it possible to multitask on modern computers.

Volatile memory is stored in a RAM modules. (Photo by Possessed

Photography on Unsplash)

Volatile memory is stored in a RAM modules. (Photo by Possessed

Photography on Unsplash)

Manual memory management

Typically in older programming languages for example, in C language you manually get a memory space with certain functions. So to get a memory of a certain quantity, you have to type how many bytes you want to allocate and free that memory space once you're done using it. To give an example of this, here is an example code written in C:

C

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

int *ptr;

int n = 5;

ptr = (int*) malloc(n * sizeof(int)); // allocate memory for 5 integers

if (ptr == NULL) {

printf("Memory allocation failed");

exit(1); // exit the program with an error code

}

// assign values to the memory block

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

*(ptr + i) = i;

}

// print the values from the memory block

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

printf("%d ", *(ptr + i));

}

free(ptr); // free the allocated memory

return 0;

}

The Malloc function takes one argument, which is the amount of memory to allocate in bytes. It then returns a pointer to the allocated block of memory. In the case of allocation, the operation is not successful, the function returns a NULL pointer. Here in the given code we've allocated 5 integer amounts of bytes to ptr and assigned values to them. Then finally we freed the allocated memory using the free function. Freeing existing memory at the last step is really important in order to prevent memory leaks. The common error people make when building large-scale codebases on these languages is that when at any point of the program, the allocated memory is not freed, the computer won't take it back because it is flagged as being used by that program. The other common mistake is when you freed the memory and you try to access that same bit of memory, in that case, the OS might have given that block to some other process and because of that, you might get compile-time errors or some random value you didn't ask for.

Photo by Denny

Müller on Unsplash

Photo by Denny

Müller on Unsplash

In this approach, as we have seen from the examples, we might encounter loads of problems. So in order to get ahead of that, most high-level programming languages have some sort of garbage collection built in. In short, garbage collection basically gives you memory when you don't need it anymore.

Ways of garbage collection

The most obvious way of garbage collection is reference counting. In this method, the allocated memory has a property called reference counter, you keep track of how many references that bit of memory has, and you free the aforementioned memory when it finally has zero references in the program. This approach has its own tradeoffs, firstly you have to remember to add or decrease this property and the other one is that with this approach you now have an integer associated with all of the memory spaces in your program which makes the program memory inefficient and can decrease the program's performance. Another problem is some sort of memory leak where you have some memory blocks with reference counter that doesn't go zero in order to free them. This in itself can be classified as a memory leak. With its tradeoffs, the reference counting is used in programming languages like Python where it's used with other sound methods of garbage collection like mark and sweep algorithm.

Mark and sweep

To understand the mark and sweep algorithm we need to know about live memory and dead memory concepts. Live memory is a memory block that is actively referenced, whereas dead memory is a memory block that doesn't have any references to it.

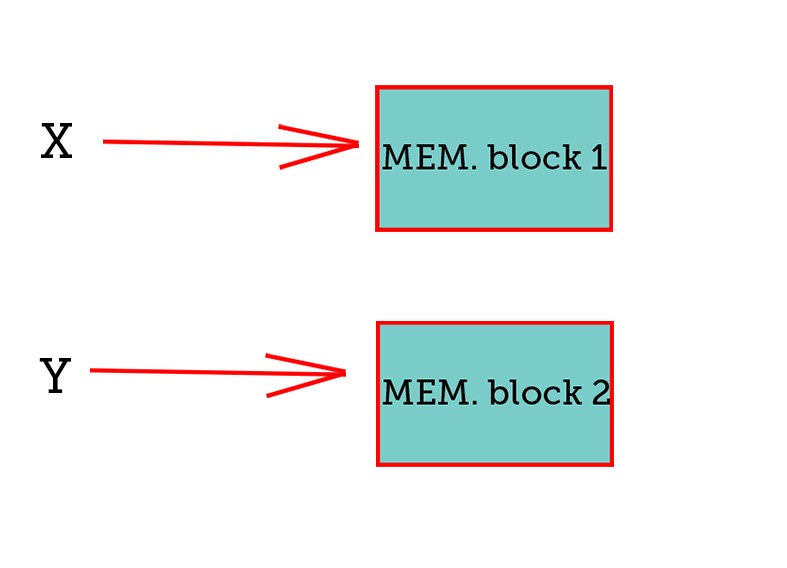

In this example, x and y is referencing memory blocks 1 and 2 so they are live memory and

therefore marked.

In this example, x and y is referencing memory blocks 1 and 2 so they are live memory and

therefore marked.

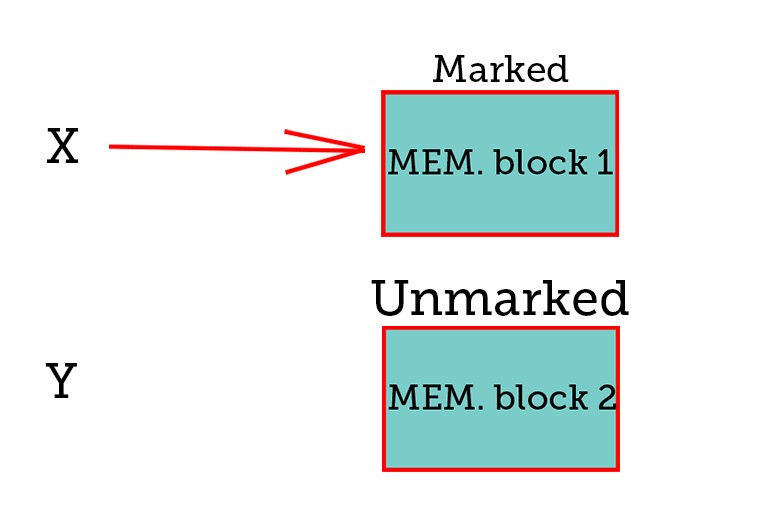

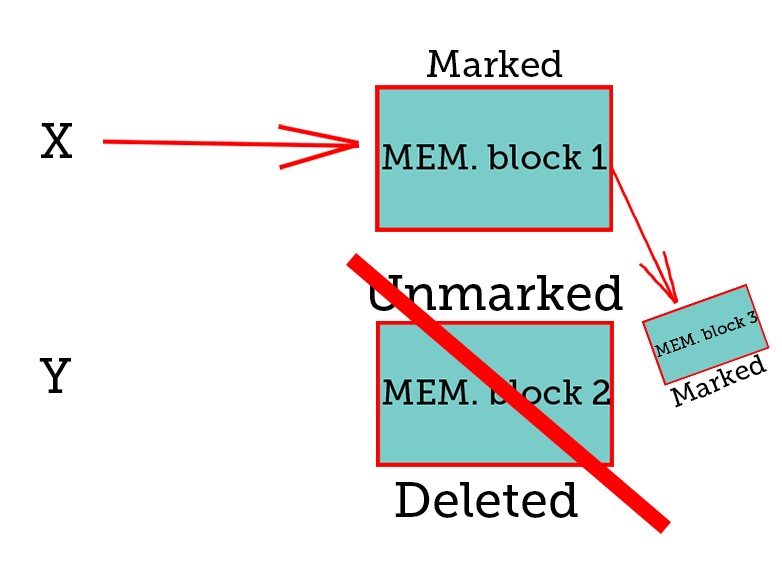

Mark stage goes through all of the accessible memory blocks, even the blocks that are not directly referenced. Here in this example if we remove the y reference to the memory block 2:

Marking goes through all the direct or indirect references marks them one by one sort of like a boolean value, because of that the program size is lower than the reference count method.

Sweeping stage frees up the unmarked memory block, making our program less dependent on high chunks of memory.

Source section

- Debnath, M. (2023) Understanding garbage collection in go, Developer.com. Available at: https://www.developer.com/languages/garbage-collection-go/ (Accessed: May 3, 2023).

- DeBrie, A. (2023) Python garbage collection: What it is and how it works, Stackify. Available at: https://stackify.com/python-garbage-collection/ (Accessed: May 3, 2023).

- Garbage collection in Java (2022) GeeksforGeeks. GeeksforGeeks. Available at: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/garbage-collection-java/ (Accessed: May 3, 2023).

- Garbage Collector Design (no date) Python Developer's Guide. Available at: https://devguide.python.org/internals/garbage-collector/ (Accessed: May 3, 2023).

- Heller, M. (2023) What is garbage collection? Automated Memory Management for your programs, InfoWorld. InfoWorld. Available at: https://www.infoworld.com/article/3685493/what-is-garbage-collection-automated-memory-management-for-your-programs.html (Accessed: May 3, 2023).